When Everything Stopped

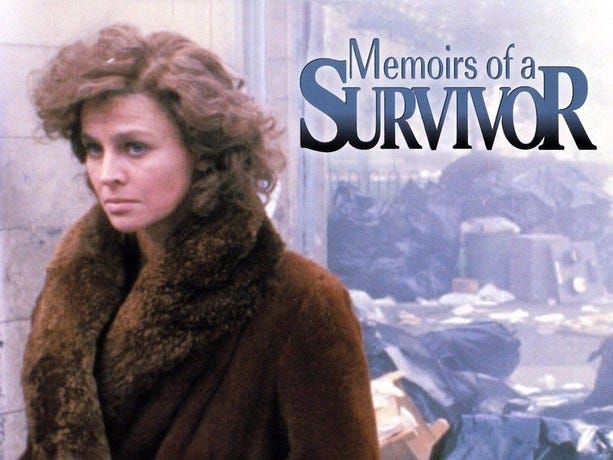

Watching Memoirs of a Survivor (1981, David Gladwell)

Author's note: I am back from Texas. In fact, I have been for about 3 months. I had intended to write more frequently while I was away, but the unnerving developments regarding social media and threats to student visas made me highly cautious about what I put out while trying to finish my research visit with minimal drama. While I plan to write more about my work in the Ransom Center archives, for now I am reawakening this substack some reflections on a very strange, very haunting Doris Lessing adaptation.

***

Perpetual war. Disintegrating communities. Unstable public services. An uneasy slow march towards the end of the world. Sound familiar? I wonder when in the past 100 years or so it wouldn't have.

In Memoirs of a Survivor (1981), adapted from Doris Lessing's 1974 novel of the same name, David Gladwell presents a nastily recognisable conception of the end of the world.

“WHEN EVERYTHING STOPPED.”

These words alone introduce the film, printed in white on a black background, before we are confronted with Gladwell’s eerie scenes of North London in the grips of a slow, stupifying apocalypse.

In this version of late 20th century London there are few clues as to how its current state materialised. Flats are empty, rubbish everywhere, electricity and running water stopped. People roam the streets in guarded, baffled parodies, scavenging and surviving, still dressed in their ordinary clothes of pre-societal collapse.

D (Julie Christie) watches from her window, warily observing the street below where gangs of young people gather around bonfires. Christie's performance is almost passive, just a discreet wrinkle of concern on her brow and she goes about the mundainaties of daily life.

Scattered newspapers on the street give hints of what happened to cause everything to stop. Perpetual war, nuclear threat, social chaos, “more hard years”. Whatever journalists produced those headlines, whatever governments informed them, they are nowhere to be seen.

Gladwell's story, like Lessing's, sticks firmly to this bleak corner of London. On the TV, before the electricity cuts out forever, D sees footage of people walking away from the city down motorways, sparse luggage in hand, but the images stop there. We never see if life persists outside of London, wherever these stragglers are heading to. More and more young people converge in front of D’s building, and after a few days camp off they set for who knows where. A woman remarks: “You never hear anything after.”

One day, D is surprised to find a man and a teenage girl in her living room. The man - some vague figure resembling a council authority - presents Emily (Leonie Mellinger) and her small dog, Hugo, into D's care.

Emily is keen for something. Her high and falsely girlish voice is jarring after the silence of D’s solo life. A teenager coming of age at what appears to be the end of civilisation, she has no security in her present nor in her future. With a rehearsed enthusiasm she sings the praises of the small room given her, invents a breakfast out of the pitiful contents of D's cupboards, tells Hugo he is her “love”. In these bursts of enthusiasm her eyes betray a frantic need: for acceptance, for a place in the world, for a future. D's distant responses and the chaos outside are the answer she is trying to ignore: her needs can no longer be met by the world they live in.

While chaos rains outside, D is sinking further and further into the fantasy of another house, just behind her wallpaper, where a grand Victorian family live.

In D’s dream house, just through the wallpaper, there is another Emily, a little girl not much liked by her family. The exaggerated Victorianisms of the stern and sinister adults that surround this other Emily seems to say something about the contemporary time of the film. She is sullen, bossed by overbearing adults, so expected to sit still and completely silent. The sinister nature of her parents’ presence is emphasised when her otherwise distant father lingers over the sleeping, naked Emily. The Victorian upper class atmosphere of coldness and cruelty present in the dream house hint to D of the possibilities of what the real Emily may have suffered in her unknown past.

The fact that this fantasy house belongs to a period before the major global wars that ripped through the twentieth century brings to mind a common theme of Lessing’s novels, that our culture as humans has burst forward with all the technical innovations of world wars, ostensibly called progress, while in the violent pushes forward we have not lost our Victorian hang ups, our societal constraints on gender and sexuality. Britain may have been revolutionised by machine guns, miniskirt, and TV, but the violent subtexts of class and oppression that are so blatant in Victoria settings continue to underpin modern life.

Eventually, the real Emily is drawn to the crowds of young people camping outside the flat, and joins the alluring Gerald in his project to set up a working household, a family, made up of all the children left behind by parents who have perished, perhaps in the wars, perhaps by disease.

At first she is delighted to be launched into the traditional mother role and plays it near-convincingly. But D, who has been an adult before “everything stopped”, can see the falsity in trying to uphold traditions of the family, of performing a version of a woman Emily can never have really seen. Eventually, Emily is trapped looking after the many needy children while Gerald moves on to new sexual partners. “We talked it over and there wasn’t going to be any of that old nonsense,” cries exhausted Emily as she de-lices child after child, “Horrible stuff: people in charge!”

Emily remembers enough of the days before the breakdown of society to be disgusted by such heirarchies, yet she has fallen into those age-old traps of gendered oppression anyway: marriage, family, housework.

In so many of Lessing’s novels, marriage is misery. In The Children of Violence (1952-1969), a coming-of-age series set in an African colony around WWII, the couples getting married multiply as war draws closer. The atmosphere of looming conflict infects them with a mad desire to run to the alter, but few of these hasty marriages are happy. Anna and Molly in The Golden Notebook (1962), widely considered Lessing's masterpiece, constantly face the judgement of Molly’s conservative ex-husband and her son Tommy for their radical politics and rejection of traditional marriage. In her first memoir, Under My Skin (1994), Lessing writes of her own marriage: ‘a graceless wedding, which I hated. […] In the wedding photographs I look a jolly young matron.’1 This marriage, like the ones in Children of Violence, was inspired by war and entirely doomed.

With no concept of what a woman is to be in this frightening space, Emily plays at the stereotypes she has seen perhaps growing up, before whatever perpetual war has absorbed the future. We see Emily experimenting with gender, adapting D's old clothes into various costumes of stereotypical womanhood. The novel goes further to destabilising concepts of gender, body, image through the character of Hugo who is in that text entirely unknown: D can never place whether the little animal is a cat or a dog. Hugo rejects categorisation.

Can D's other world, the world through the wallpaper, offer a chance for Emily to have her needs met? As the film draws to a close, D is drawn further into this world. In the once ornate rooms she now finds smashed china, ruined furniture, destroyed flower beds. This kind of damage looks man-made. Is someone in the wallpaper world tearing it down on purpose? In the closing scenes, the world beings to be populated by those unfortunate children who recently had populated the real world but had passed away.

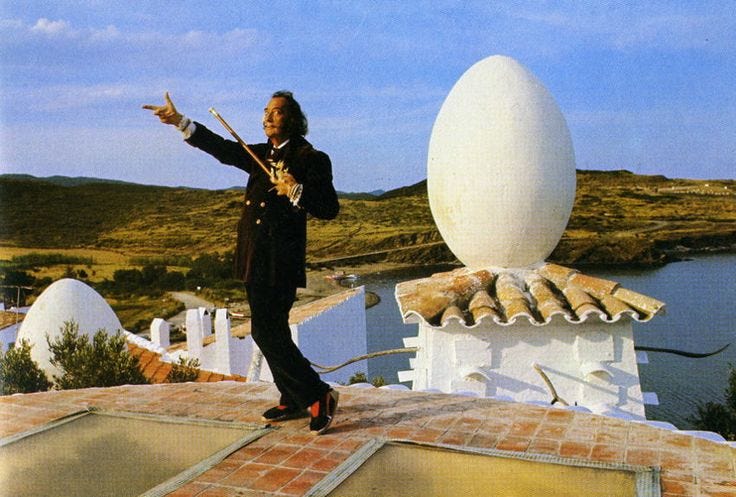

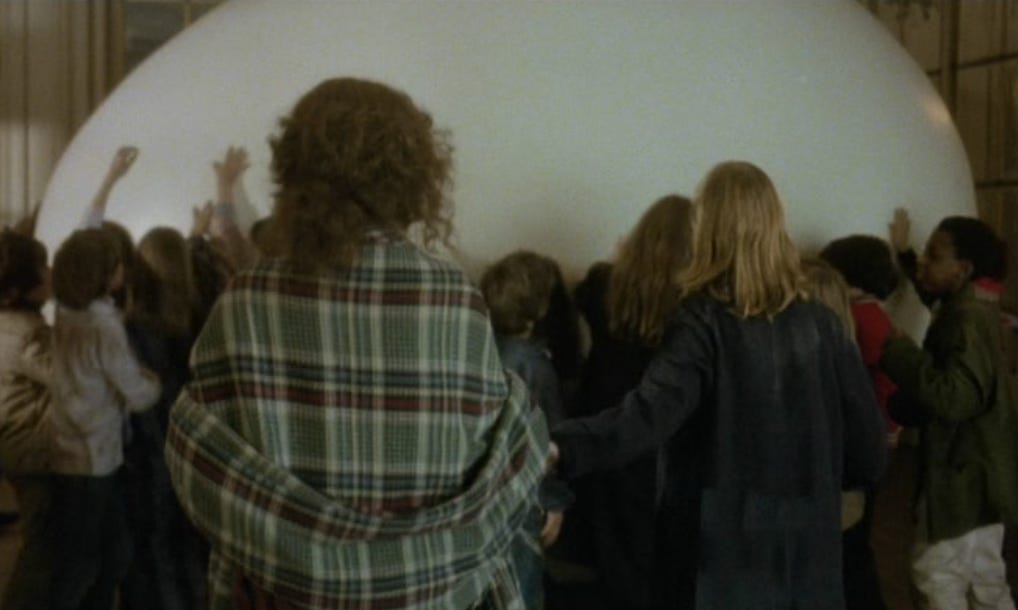

Suddenly, Gladwell's realist images of this apocalyptic future are disrupted by the absurd. In the centre of the house there appears a giant white egg. The children surround it, touching it, excited by whatever it contains. Passing the egg's smooth curves D is disturbed to find, amongst the children, her own self, smiling and content in this other world. What the egg means remains unexplained. The inpenetriability of the egg, which never hatches during the film's progress, is at once promising and disturbing. Perhaps Lessing and Gladwell use it like Dali, a “sublime myth”2 which signifies new life, potential, something new being born. Or does it signify the continuance of the society that has caused so much destruction?

Here, in this uncertain place, the second D and the children appear happy, clean, and nourished, in a way they never were back where “everything stopped.” Seeing this, D convinces her surviving friends to cross over into the wallpaper.

Perhaps beyond the wallpaper, where genteel Britishness has been so firmly destroyed, D thinks that they can all find what they desire, forever.

I love this, will definitely seek this adaptation out! (and I also need to read any Doris Lesssing because that is a serious blindspot of mine!)